How Medical Documentation Shapes Justice in Personal Injury

Part 2: Uniqueness and The Human Side of Traumatic Injury

Welcome back.

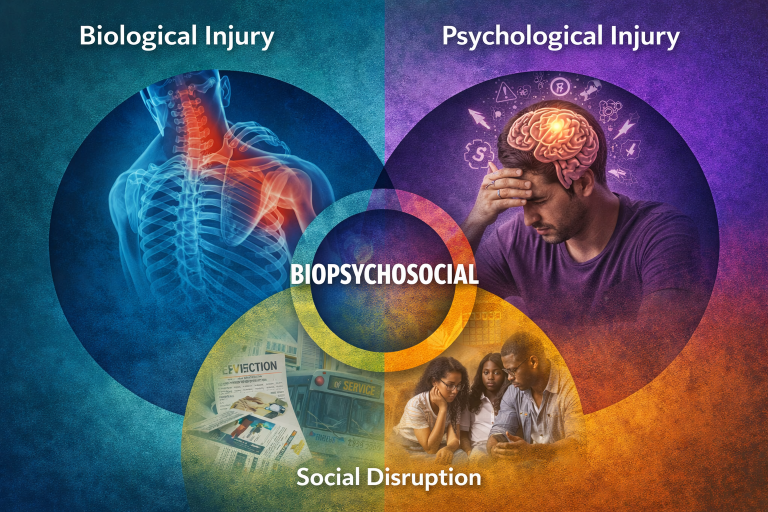

In Part 1, we focused on laying the structural foundation of strong PI documentation: how to begin the process with accuracy, strategy, and intention. Now, in Part 2, we take a deeper turn. We move from structure to story, because great documentation doesn’t just record pain, it explains why that pain matters for this unique patient.

It’s time to shift your perspective from injury to impact.

In clinical medicine, you’re often taught to emphasize objectivity through numbers, tests, and measurements. And while those are essential, especially in personal injury, they’re not enough.

Objective findings without human context are like building the outer structure of a similar-looking house without the unique interior that reflects the owner. The details of the story—the vulnerabilities, the recovery challenges, the day-to-day life limitations—these are what transform your records from medically sound to legally powerful.

This is how you become a PI value driver.

Because here’s the truth: the same injury does not affect every person the same way. A healthy 24-year-old jogger might bounce back from a rear-end collision in three weeks. But a 60-year-old elementary school teacher with cervical spondylosis and diabetes? That patient might need six months of care.

While both stories may be medically valid, it’s the medical uniqueness that is the differentiator.

That’s where your documentation becomes the bridge. Not just between symptom and treatment, but between trauma and understanding.

Let’s dive into the next five (out of 20) documentation practices that will help you humanize the chart and strengthen the case for your care, your billing and the patient’s recovery:

6. Note Pre-Existing Conditions and Vulnerabilities

Too many providers fear documenting pre-existing issues. They assume it will hurt the case. In fact, when done right, it helps. Greatly.

Why? Because real people aren’t perfect. And in PI, the “eggshell plaintiff” rule says a person must be taken as they are, not as an idealized version of health. If a patient had prior lumbar degeneration and a slip-and-fall worsened it, you’re not undermining the case by acknowledging it. You’re giving it depth and credibility.

Write: “Patient with known lumbar disc degeneration presents with worsened symptoms following fall; unable to …. (detail the ADLS) for extended periods.” That tells a jury exactly why this incident had such a significant impact on this person’s quality of life: “pain and suffering.”

7. Ensure Exam Findings Align with Patient Complaints

One of the easiest ways for an adjuster or defense attorney to discredit your record is by pointing out inconsistencies. If a patient says their headaches are severe, but there’s no exam of the cervical spine or neurological system, your record falls flat.

Subjective complaints must be mirrored by objective effort. That means documenting ROM tests, orthopedic signs, neurological screenings, palpation findings—anything that supports the complaint.

If a patient reports ongoing dizziness post-collision, and your exam reflects cranial nerve involvement or cervicogenic triggers, the chart now tells the same story from both sides—subjective and objective. That’s how you build trust in your documentation.

8. Avoid Generic, “Cookie-Cutter” Treatment Plans

If every patient receives 3x/week for 4 weeks, re-eval, taper to 2x/week—your notes start to look less like treatment and more like a factory line.

Patients, conditions, and healing speeds vary. Your plan should reflect that.

For instance, an acute whiplash case may start with passive modalities like EMS and cryotherapy. But as inflammation subsides, you should show a shift to active therapy—stretching, resistance work, proprioceptive training. And most importantly, document the rationale behind those changes.

Write: “Patient progressed from passive to active therapy due to reduced inflammation and improved pain tolerance.” That kind of logic makes your treatment plan look personalized, not templated.

The same goes with the need for interventional pain treatments or surgery. Reflect the unique patient factors requiring the unique medical intervention to address the patient’s pain. Often the medical treatment path is one of elevation as lesser treatments prove ineffective or insufficient. Even then, higher interventions such as surgery also sometimes involve the need for extended rehabilitation.

Unique people require unique treatment. Your documentation should be focused accordingly.

9. Avoid Templated SOAP Notes

This one is simple. “Patient tolerated treatment well. No complaints.” That sentence? It’s the enemy of PI credibility.

If you’re using EHR macros or Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools, that’s fine, but customize them every single time. Add in changes in symptoms. Adjust treatment based on feedback. Include specific ADLs (Activities of Daily Living) impacted and the return to pre-injury status: “Patient states she was able to vacuum one room of the house for the first time since the accident, though experienced increased soreness afterward so stopped at one room.”

These quotes are gold in a courtroom. They make your patient relatable. They show progress, or lack of it, in a way no ROM number ever could.

10. Use Patient-Specific Goals

Goals aren’t just about treatment outcomes. They are evidence of unique patient-centered care.

Instead of vague goals like “reduce pain” or “increase ROM,” use specific, functional targets. “Return to lifting 20lbs. overhead at work.” “Resume driving without pain after 30 minutes.” “Regain ability to throw baseball overhand with grandchild.” “Regain ability to put on own makeup and dress self.”

Then, revisit those goals every 2 to 4 weeks. Did the patient progress? If not, explain why. Maybe it’s because of delayed healing. Maybe emotional distress is a barrier. This level of documentation doesn’t just support the medical case, it supports the human one.

Final Takeaway for Part 2

This is where medical meets meaningful. Your documentation must show that your patient isn’t just another case. It’s a person whose life has been disrupted and perhaps even destroyed.

Pre-existing conditions don’t weaken the story, they provide context. Care plan changes don’t look erratic, they show responsiveness. And SOAP note personalization isn’t fluff, it’s the narrative thread that connects pain to impact.

In PI, the strongest documentation is both clinical and personal. So, treat your patient like a person, and chart them like one, too.

In Part 3, we’ll turn to the silent killers of credibility: care gaps, undocumented referrals, and vague justifications. We’ll learn how to close those gaps and keep the case airtight.